Among the results was the Macedonian Opera and Ballet, designed in 1968 by Štefan Kacin, Jurij Princes, Bogdan Splinder, and Marjan Uršic. An international conclave of architects converged on Skopje, Macedonia, after its near-total obliteration in a 1963 earthquake. Yugoslavia barely figures in the Western Euro-American account of modern architecture, and one of the curators’ missions is to overturn a modern canon that MoMA helped codify.

As the nation rebuilt its bombed and earthquake-flattened cities, it produced a mixture of modernist dead zones, with vast plazas framed by oppressive megastructures and more-humane new versions of old towns.

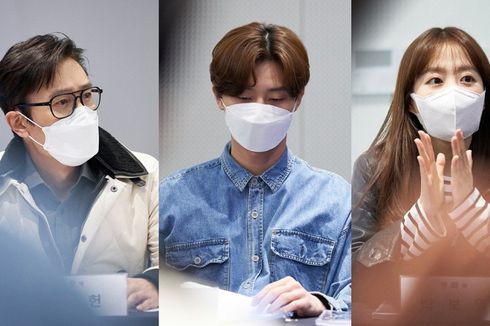

#CONCRETE UTOPIA MOVIE TV#

The Avala TV tower sprang skyward on graceful concrete legs. Milan Mihelic celebrated the country’s new love of cars by supporting the roof of his Petrol gas station in Ljubljana, Slovenia, with an exuberant concrete tree. The almost-world-champion Croatian soccer team still plays in Boris Magaš’s Poljud Stadium in Split, a gracefully shallow concrete bowl nested in the earth and canopied by a great steel trellis on either side. Slender tubes, levitating slabs, Y-shaped columns, flamboyant cantilevers, undulating walls, rough surfaces - these avant-garde elements had bold Balkan counterparts. They learned from Le Corbusier, Paul Rudolph, and Marcel Breuer and pushed concrete to expressive extremes, forging their own brand of theatrical brutalism.

With the government, the military, and local councils as their enthusiastic clients, architects translated socialist aspirations into power plants, housing blocs, museums, and monuments. The show covers the decades between that schism and Tito’s death, a period that yielded a cornucopia of architectural experiments, some poetic, others surreally misjudged. In 1948, Yugoslavia’s leader, Josip Broz Tito, split with Stalin and yanked his country out from behind the Iron Curtain. Marshaling hundreds of drawings, models, plans, and photographs, extracted from rapidly vanishing archives, MoMA presents Yugoslavia as a paradise for the politically engaged architect. Curators Martino Stierli and Vladimir Kulic, with assistance from Anna Kats, focus less on the Toward part of the title and more on Utopia. A hugely ambitious and revelatory new show, Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980, portrays an idiosyncratic, multiethnic, and open postwar society that propelled itself into the industrial age with brio. MoMA would like to flip the association, linking the name of a vanished nation to memories of optimism and impassioned building. Today, the word has acquired the resonance of antiquity, like Dahomey and Mesopotamia. In the early 1990s, Yugoslavia was shorthand for destruction: blasted cities in the heart of Europe, pulverized minarets and toppled bell towers, a whole cosmopolitan society splintered by savagery. Photo: Valentin Jeck/courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)